this post was submitted on 14 Nov 2023

206 points (100.0% liked)

Science

22875 readers

7 users here now

Welcome to Hexbear's science community!

Subscribe to see posts about research and scientific coverage of current events

No distasteful shitposting, pseudoscience, or COVID-19 misinformation.

founded 4 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

This is literally chuds argument for defunding nasa.

"I dont understand it so it's worthless to me"

the difference is with nasa we can name dozens of advancements that help people off the top of our heads but i cant even get someone to name something theoretical that might help the common man from the confirmation of the higgs-boson

so, maybe help out with that, what theoretically can we hope that we might improve our lives through confirming that particle

additionally chuds want to defund nasa to fund the military and prisons whereas id use the money from that particle thing to house homeless or invest in indigenous communities

so in short suck it nerd because it is in fact worthless to me, personally

Although I'm highly sympathetic to this argument until we have much better material conditions in socialism, I think your argument misses a significant dialectical process which must be taken into account and a reason that fundamental research is still necessary and good most of the time. Namely, the quantity -> quality relation. Fundamental research seems to have little effect until it's quantity reaches a threshold where it becomes obvious how it can be used and what sort of benefits there will be in using it, whereupon the quality of that research shifts to no longer being called "fundamental research" and becomes now its own field of research or applied research. Finding where these will appear is a difficult, though hopefully possible, endeavor.

If you argument is that fundamental research in particles will never result in that shift, I'm excited to hear how you reasoned that no contradiction/drive in the dialectics of nature found by colliders will be useful to our material conditions. I suspect you may be right but don't think I'm one who could possibly credibly say so, and therefore don't claim that it's useless.

If your argument is that fundamental research is too far away from results to make such decisions, i would really like to hear how we measure and understand this, because it feels like you know more about the threshold than me.

If your argument is that we should not focus on that when problems exist now: this is true, but can we possibly even call this focus? The money is miniscule in relation to the huge sums elsewhere and your focus on this is the real problem. You're then not necessarily wrong, but you're not fighting the most important fights.

The study of molecules was fruitful once chemical relations started being understood and used and resulted in some people "wasting time" on studying atoms. Those theories were useless except to probe what chemicists were doing already. Until the understanding reached a point that its exploitation became possible. Then the researchers were doing a science to utilize the energy of those atoms beyond the point where chemistry could apply as a framework. When this will occur again I don't dare claim.

I'm not the original person you responded to, I just found your reasoning incorrect in asking for "ways it'll help" as if that concrete answer can be given easily without deep expertise. Or even as if that can be said concretely. It's missing the way the dialectical movement from quantity to quality works. I wouldn't be surprised if, in a hundred years, fundamental research into the particles instead finds a contradiction in the way we understand them which can be exploited for energy. We have many precedents for that at every major "level" above that.

This is the type of research that can advance more immediate research into non-fossil fuel energy.

specifically, how?

Earlier versions of this same science helped us understand the theory behind nuclear power, then eventually engineer nuclear reactors. Neither of us know enough about physics to do much beyond extending that analogy into the future.

we accomplished all of that with the theoreticals, ie, without any of the physical proofs that the colliders provide (and havent provided in some cases)

also, there is criticism from actual physicists over these colliders as well and no not just that wierd lady with the accent who sucks

i find it strange for people to be like "oh you cant know what good it'll do for us in the future but i cant explain becuase none of us know enough about it" and dismiss me because im doubtful of its benefit because sometimes science just doesnt pan out, like sometimes theories are wrong and we could actually just be wasting a shit ton of money and resources to try and prove theories that are bunk

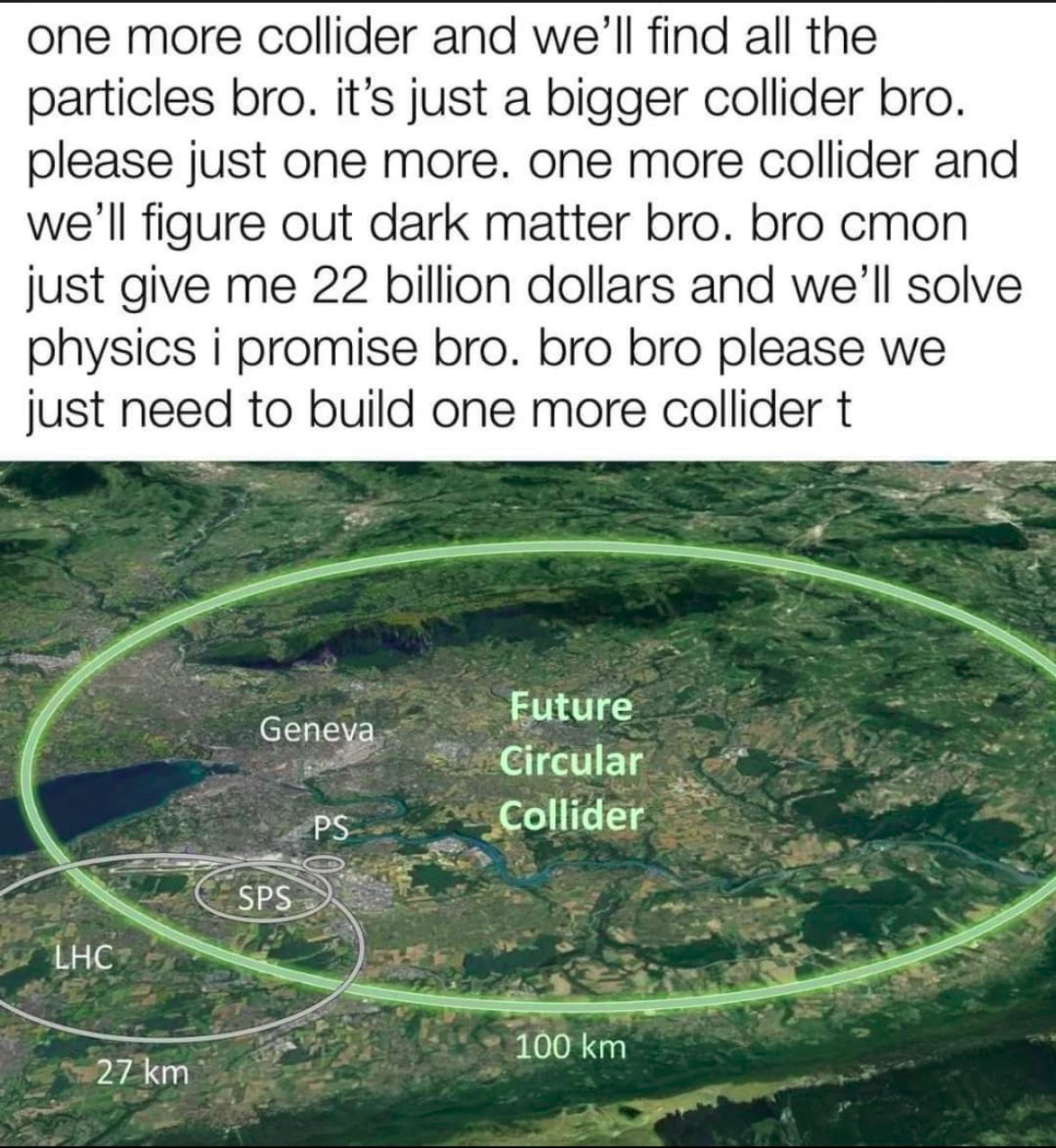

think of my point of view: we spend money on a collider to find a particle we already strongly suspect exists. cant find it. we spend money on a larger one. cant find it. spend money on a larger one, cool we found it! we confirmed what we already knew but it didnt answer a question we had. there must be something else. return to step one. so, maybe eventually we find what we are looking for. or maybe we dont. or maybe we do but realize it is not possible to interact with the thing in any ways that is useful outside of some obscure physics maths. but how many colliders do we build until enough is enough? we may very well be on a wild goose chase. what im saying is it is also possible that this stuff has as much scientific value to our real lives as elon launching a car into orbit

...No. There were plenty of tests, for example the atomic pile built at the University of Chicago. They certainly didn't just do a bunch of math and then build an industrial nuclear power plant on the first go.

I don't think you're making the same criticisms they are (I last read some of those criticisms a while ago, though).

they literally did do that

the first particle accelerator was built like over a decade later

I'm not saying a particle accelerator was used to test the theoretical underpinnings of nuclear power. I'm saying testing was done, that is, they did not "accomplish[] all of that with the theoreticals." They just used earlier tools.

To test modern physics, many (not all) physicists say the tool they need is an accelerator.