Mr. Smile's Last Laugh

How The Communist Resistance Took Out One of Denmark's Most Dangerous Nazi Snitches

Nothing seemed out of the ordinary on the morning of February 23rd, 1945 at Café 44 in Copenhagen's Nørrebro neighborhood. Around 10 o'clock, the owner, Henning Walthing, unlocked the door and entered alongside an elderly man. Shortly after, two patrons entered and ordered beer. A little later, two more men arrived. When Walthing emerged from the basement carrying supplies, the scene shifted dramatically. Two of the guests produced guns, held him up, and searched him. They found a loaded, unlocked pistol and a wallet containing a large amount of money.

Walthing was no ordinary café owner. To his Nazi associates in the Svend Staahl Group, he was known as "Walther Smile," or simply "Mr. Smile." He was a notorious and lethal informant. The elderly man was merely a bystander. The other four men in the café were resistance fighters from the communist resistance group BOPA delivering long-overdue justice.

The resistance fighters handed the wallet to the elderly man, instructing him to deliver it to Mr. Smile's mother and instructed him to wait 30 minutes before alerting anyone. They then drove off in a borrowed van with their prisoner.

It was common for the resistance not to seize money during operations like these. While the money could have funded their struggle, taking it would make it easy for Nazi propaganda to paint the resistance as common criminals and to mask resistance as robberies. Leaving the money sent a clear signal: this was a political action, not a robbery.

The elderly man did as instructed, and waited 30 minutes before reporting the incident to the municipal guard corps at a nearby police station. The guards accepted the wallet and handed it over to an associate of Walthing.

Compared to other Nazi-occupied nations, Denmark experienced a relatively mild occupation. Following their quick defeat of Denmark in 1940, German authorities pursued a "peacetime occupation," allowing Danish civil institutions to function relatively undisturbed. Large-scale destruction and imposition of direct Nazi rule was avoided. In exchange the Germans gained access to vital agricultural exports and control of their northern flank with minimal troop commitment. Initially Danish police supported this collaboration, actively hunting resistance members and rounding up refugees. However, as the tide of war turned and resistance swelled, the police increasingly shifted allegiance. By September 1944, frustrated by the police's perceived lack of cooperation, the Germans dissolved the force. Approximately 2,000 officers from major cities were deported to German concentration camps.

With the police dismantled, law enforcement was taken over by German forces such as the Gestapo and their collaborators in the hated HIPO corps (Hilfspolizei). HIPO was composed of Danish Nazi sympathizers, many of them returning Wffen-SS war criminals from the Eastern Front, tasked with doing the Nazis’ dirty work. The Nazis were only concerned with hunting the resistance and civilian law enforcement devolved into poorly trained municipal guards, civilians equiped only with batons and armbands, barely capable of breaking up fights or apprehending petty criminals caught in the act.

Amidst this chaos, the Svend Staahl Group operated. It emerged from a network of about 80 Nazi-sympathizing police officers. While the Danish police was largely anti-communist and reactionary, their nationalism made explicit Nazism unpopular, especially after the occupation, leading the Nazi officers to be shunned by their colleagues. By August 1943, in the lead-up to Germany’s declaration of martial law, roughly 30–35 of them organized into what became known as the Svend Staahl Group. These were not opportunists, they were ideological Nazis, virulent anti-communists with deep ties to the German intelligence apparatus. Many had been recruited by the Abwehr long before the group’s creation, and many were also active in other Nazi groups such as the HIPO and the Schalburg Corps – an organization of Danish Waffen-SS war criminals acting as a replacement for the embarassing failure that was the Danish Nazi Party (DNSAP).

Operating under the Schalburg Corps’ intelligence division, the Staahl Group used their positions in the police to spy on colleagues, report dissent, and feed intelligence to their German handlers. After the police were dismantled in 1944, they exploited their training and uniforms to infiltrate resistance cells. Public sympathy for the now-dissolved police force gave them cover: a glimpse of a badge sewn discreetly into the inside of a lapel was often enough to waive the usual background checks.

In the chaotic months that followed liberation, the Staahl Group was widely suspected of involvement in a wave of retaliatory assassinations carried out against resistance fighters. But these turned out to be the work of the more infamous Peter Group, a separate gang of collaborators. Unlike the Peter Group, the Staahl Group operated in deep secrecy, avoiding public raids and keeping their identities hidden. Their efforts served the Abwehr as much as they did the Nazi counter-resistance. They communicated with German forces and the Schalburg Corps through intermediaries to minimize exposure.

Their leader, Svend Staahl, real name Poul Otto Ditlev Nielsen, was a ghost. He reportedly bragged that the resistance would never catch him and claimed he’d kill anyone who suspected his true allegiance. Rumors circulated that he had already murdered six or seven men to keep his cover intact.

Nicknamed "Pretty Walthing" for his dapper style, Mr. Smile had been a committed Nazi since 1937 and once served as adjutant to Danish Nazi leader Frits Clausen. After the German crackdown on the Danish police in September 1944, he became second-in-command of the Svend Staahl Group. Funded by the occupiers, he opened Café 44 in the heart of Nørrebro, a known stronghold of the communist resistance. Feigning sympathy to the resistance, Walthing used the café as a front to gather intelligence, which he funneled to the Germans through the Staahl Group.

By December 1944, the resistance had identified both the group and an apartment they used as a meeting point. The Staahl Group posed a deadly threat: resistance fighters they exposed faced torture, deportation to concentration camps or execution. The group had to be eliminated. A liquidation team from BOPA was assigned the task.

At the time, many believed such liquidation orders came from the Freedom Council, the underground body coordinating Denmark's resistance. One participant later recalled in his memoirs that the group had been "sentenced to death" by the council’s liquidation committee. In truth, no such committee existed. For security reasons, fighters remained unaware of organizational details. Instead, liquidation decisions were taken by local leaders within individual groups like BOPA.

The team surveilled both the apartment and Café 44, aware of Mr. Smile’s key role. One BOPA member became a regular patron at the café, earning the trust of Walthing’s mother, Agnes, who worked there by offering her a black market deal for coke rationing stamps and was able to confirm Mr. Smile's identity.

Tracking the group proved difficult. The apartment was often empty, and when used, the collaborators slipped into traffic to evade pursuit. It took time to decipher the routines they followed to assemble discreetly. Just days before the planned raid, the resistance finally tailed a group member to the police guard post at Amalienborg Palace. They made a big mistake by asking the police for help identifying him from a photo. The police delayed, and one way or the other the Staahl Group caught suspicion they were being hunted, and abandoned the apartment. With the opportunity to strike the whole group lost, BOPA shifted its focus to targeting known individuals.

After his abduction, Mr. Smile was taken to the basement laundry room of a borrowed villa in a Copenhagen suburb. There, he was guarded while senior BOPA members were summoned for interrogation. Interrogations of captured collaborators was rare, but Mr. Smile was believed to possess critical intelligence.

He quickly recovered from the shock. Over the four hours he waited in the basement, the smooth-talking informant insisted on his innocence with such flair and conviction that his guards began to believe him. They assured him he had nothing to fear—he merely had to wait for questioning.

The interrogation was conducted by senior BOPA members Børge Thing (codename Brandt) and Erling Andresen (Lund). Andresen, a jurist and prosecutor with the Copenhagen Police, took the lead. Neither interrogator knew precisely whom Mr. Smile had informed on, only that he was a key member of the Staahl Group. Thing remained mostly silent except for once when he snapped, “You are fucking full of shit!” at Mr. Smile, a blunt interruption to what he felt was Andresen’s overly polite line of questioning.

Remarkably, the interrogation was filmed on silent film. The footage shows a well-dressed Mr. Smile in his fedora and overcoat, seated among dusty potted plants and laundry supplies in the basement. According to those present, no physical torture was used. The film corroborates this, showing no signs of violence.

At first, Mr. Smile denied everything. He claimed never to have heard of Svend Staahl. He asserted the pistol was merely for protection due to a past threat. He remained calm and one account describe him as "acting with the utmost servility and smarminess." However, when asked if he knew "Walther Smile," he turned pale. The resistance knew his codename. The game was up. He began talking.

He admitted to knowing Svend Staahl and revealed his real name. He confirmed he had been at the apartment but claimed his role was purely clerical. The interrogators told him he might be evacuated to neutral Sweden if he cooperated fully. He continued to deny snitching on anyone. He could not explain how he got the money used to open Café 44, funds the resistance knew had come from the Germans.

Then he made a fatal mistake.

He claimed to have told another group member about a young man involved in the resistance, arguing this somehow proved his innocence because he could have told the Gestapo about him but didn't. The young man in question happened to be the brother of interrogator Erling Andresen. He had been wanted by the Gestapo, and his evasion was certainly not due to Mr. Smile's restraint.

After an hour and a half of questioning, Mr. Smile had given up a few names and addresses, but it was clear he would divulge no more useful information. He had confessed to being part of the Svend Staahl Group and admitted to informing on at least one resistance member. It was enough. No one present doubted his guilt anymore or the inevitability of what came next. Mr. Smile, however, still clung to the belief that he would be taken to Sweden. The BOPA team maintained this illusion to keep him cooperative. They told him Svend Staahl had been captured and he would be taken to meet him to corroborate his version of events.

They drove him north, to a forest outside Copenhagen. Upon arrival, they told him they would need to walk a short distance through the forest to reach Staahl. Mr. Smile complied without hesitation, delicately stepping around puddles to avoid soiling his expensive shoes, apparently still unaware of what awaited him.

Then, on a muddy woodland path, two resistance fighters silently raised their weapons and fired from behind. A bullet snapped his neck and he died instantly. He collapsed face-down in the mud with a soft sigh.

The execution did not end there. One of the fighters, code-named "Moe", cracked under the psychological weight of the moment. Consumed by rage and revulsion, he emptied the rest of his pistol into the corpse. Andresen, a trained prosecutor, later described it as "a blood frenzy" and considered it far more chilling than the killing itself.

With Mr. Smile dead, BOPA turned its sights to Svend Staahl. They now knew his real identity and considered him the next target. But events took an unexpected turn.

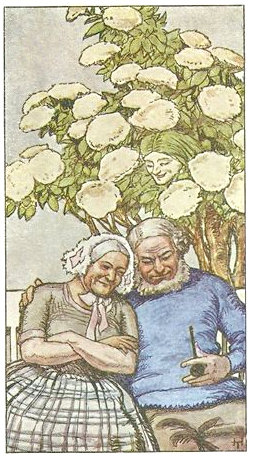

When Staahl learned of Mr. Smile’s abduction, he panicked. Convinced that he was next, he barricaded himself inside the apartment of Mr. Smile's mother Agnes Walthing, a known meeting place for his group. Alongside him were Agnes Walthing and three other members, all fearing a resistance raid.

That afternoon, they phoned the HIPO corps at the central Copenhagen police station and requested reinforcements. A protocol was agreed upon: the HIPO men would knock five times, and Staahl would respond with a password to confirm their identity. Simple. Foolproof.

When the HIPO arrived, they knocked as planned. But Staahl forgot about the password and began opening the door without saying a word. The HIPO officer outside, jittery and expecting an ambush, opened fire with his machine pistol. Bullets shredded the wooden door, striking both Staahl and Walthing. They died instantly.

In a twist of fate, equal parts poetic justice and bloody slapstick, one gang of Nazis had accidentally wiped out another. Svend Staahl’s final boast had come true: the resistance never got him. His own carelessness and the paranoia of his fellow Nazis did.

The aftermath was bloody. In retaliation, German forces executed several civilians. In total, 21 people died violently on February 23rd, 1945, in connection with the Staahl Group.

Over the following months, the resistance hunted down and liquidated several remaining members of the group. Some members took refuge inside Copenhagen's central police station, hoping proximity to the HIPO corps would shield them. Others, sensing the war was nearly lost, tried to switch sides and ingratiate themselves with resistance circles.

After the liberation, known survivors were expelled from the police and sentenced to up to 16 years in prison for treason.

Although the Staahl Group is believed to have laid the groundwork for numerous German actions against the Danish resistance, details remain scarce and very little is known about their work for the Abwehr. The German police successfully destroyed most of their records shortly before capitulation.

Imagine being so racist that Germans and Swedes are not white enough for you.