Due to another user’s request, I have decided to compile threads on fascism, profascism, Japanese Imperialism, & neofascism here for your convenience. This compilation is, of course, incomplete, & its structure is subject to eventual change, but I hope that it suffices.

Origins

- German towns & cities with a history of medieval pogroms were likelier to support Fascism

- The History of Fascism in Ukraine, with Prof. Barry Lituchy

- The U.S.’s many influences on German Fascism: The colonization of North America inspired the Third Reich & the Third Reich’s Chancellor was inspired by racist ‘Wild West’ stories

- How the Second Reich’s Colonialism in Africa Incubated Ideas & Methods Adopted & Developed by the Third Reich

- How European imperialism in general influenced the Third Reich’s imperialism in particular

- The Armenian Genocide inspired the Third Reich

- Really Existing Fascism

- Why Mussolini shifted from socialism to Fascism

- How World War I created Fascism

- The History of Fascism in Ukraine, Pt. I: The Origins of the OUN, 1917–1941

- Crash course on the Freikorps: social democracy’s pawns & German Fascism’s heritage

- Many of the Gestapo’s leading officials also worked for the Weimar Republic

Economics

- The Functions of Fascism, a monologue by Michael Parenti (highly recommended)

- The Corporate State in Action

- White‐collar workers in Italy from the Liberal to the Fascist era

- The Fascists promoted ‘class collaboration’ over class struggle

- The first privatisation: Selling SOEs & privatising public monopolies in Fascist Italy (1922–1925)

- The advertising industry flourished under Fascism; many Fascist advertisers learned their techniques from the U.S.

- Imperial capitalists once marketed products based on three accidental deaths

- In Fascist Italy, state interference in the private sector was minimal; a refutation of the old ‘fascism is socialism’ nonsense…from 1936

- Analysis of the Fascist colonization of Libya

- Analysis on the recruitment of Italian proletarians to Eritrea under Fascism

- The Anglo‐American ruling classes wiped out Fascist Italy’s WWI debts; in the 1920s, the American govt. effectively forgave 80.4% of Fascist Italy’s war debt

- Fascist Italy’s economy was directly influenced by Morgan Bank

- How nutrition worsened under Fascism

- How the Fascists handled unemployment

- London supported Fascism’s intrusion into Albania’s economy

- The most shockingly honest summary of Fascism that you’ll see from capitalists

- Against the Mainstream: Fascist Privatization in 1930s Germany

- The Fascist prehistory of the shoes & sportswear company Adidas

- The Third Reich was not a planned economy

- The transfer of Jewish‐owned property into “Aryan” hands was at first left to private initiative

- The Weimar Republican origins of the Reich’s “welfare” bureaucracy & its use to the Fascist bourgeoisie

- The Workers’ Opposition in the Third Reich; the folly of the Third Reich’s ‘Strength through Joy’ initiative; street politics in Hamburg & the lower‐class struggle against anticommunism, 1932–3

- How petty bourgeois white musicians benefitted from German Fascism

- Adolf Schicklgruber’s capitalism

- The Third Reich supplied Tel Aviv with building materials & funded most of the Zionist settlements in Palestine from 1933 to 1941, which included some prefabricated buildings

- Zionists became distribution agents for Fascist products all over the Middle East & North Africa; Zionism rendered the Jewish boycott on German goods useless

- British bankers extended credits to the Third Reich

- Consumer research in the Third Reich was based on that in the U.S.

- Tobacco policies (or the want thereof) in the Third Reich

- Fascist Beanie Babies

- Recruitment & coercion in Imperial Japan: evidence from colonial Karafuto’s forestry & construction industries

- The secret behind Fascist Italy’s food self‐sufficiency (and no, just because a country is food self‐sufficient doesn’t mean that everybody is eating well)

- The Fascists were forced to rely on Ethiopian labor to feed white colonists

- Fascist‐occupied E. Africa received 26.9% of its oil from the U.S. in 1935

- An analysis of the Fascist takeover & segregation of an Ethiopian marketplace

- Analysis of the white proletariat in E. Africa under its Fascist occupation

- Britain exported considerable quantities of scrap metal to the Third Reich

- U.S. capitalists supplied Japanese Imperialists

- The Third Reich was the source of 60% of all investment in Zionist‐occupied Palestine from 1933–1939

- Southeastern European capitalists willingly supported antisemitism & Southeastern European capitalists benefited the Third Reich’s rearmament tremendously

- The Third Reich made it easy for landlords to evict Jewish tenants

- How Allied capitalists supplied Fascist Germany throughout WWII; corporate America’s support for the Third Reich was so crucial that the U.S. might as well have been an Axis power; these American corporations aided the Third Reich

- Liberal capitalists greatly rearmed prefascist Romania, which traded heavily with Fascist states

- Native banks in Zhejiang prospered under Axis occupation

- Norwegian capitalists asked Fascists to forge letters saying that they were ‘forced’ to collaborate

- How Danish capitalists willingly collaborated with the Third Reich; more than one thousand Danish capitalists happily assisted the Third Reich

- The Third Reich interfered minimally in France’s private sector

- Netherlandish capitalists willingly collaborated with the Third Reich

- Swiss capitalism was critical to the Third Reich

- Antisemitism made Bulgarian capitalists richer

- Portugal & the Third Reich’s Gold

- Finland was the Third Reich’s only ally that was allowed to buy German goods on credit

- The Cloaking of Fascist Assets Abroad, 1936–1945

- Gold, Debt & the Quest for Monetary Order: The Fascist Campaign to Integrate Europe in 1940

- Finnish–Fascist Relations & the Diplomacy of the Petsamo Question, March–December 1940

- Fascist officials & SS commanders amassed personal fortunes

- The Empire of Japan employed millions of child laborers

- How the Axis (partially) caused famines in Vietnam & Java

- Why fellow capitalists bailed out Axis businessman Alfried Krupp

- The labour movement & business élites under fascist dictator Francisco Franco, 1939–1951

Culture

- Why Fascism (mostly) opposed Freemasonry

- How Fascism Ruled Women; the Fascists mobilized women for their colonization of Ethiopia; Women & Alcohol Consumption in Fascist Italy

- Corporal punishment & psychological violence were common in Fascist Italy’s rural schools

- How the Fascists altered the ancient landscape of Rome to fit their agenda

- How Fascist Italy suppressed abortion

- Fascist propaganda in pre‐1933 Germany

- The history of the fascist motto ‘Slava Ukraini’

- Hermann Göring predicted that ‘nobody in Germany will know what Marxism is’ by 1983

- Policing under German Fascism

- ‘Race, military training, leadership, religion! These are the four unshakable foundations of [German Fascism’s] education!’

- Christmas under the Third Reich

- Fascists normalized imperialism for children with games, playthings, & even dishware

- There were competing factions in the Third Reich’s govt.

- Police propaganda (copaganda) in Europe’s Fascist empires

- Redefining the Individual in Berlin, 1930–1945

- Archaeology confirms that…the Fascists avoided African cuisine like the fucking plague

- The Third Reich strongly discouraged marriages & sexual relations with Italians (even during Axis membership)

- The Fascists built a zoo right next to one of their concentration camps

- The Fascists intentionally built a merry‐go‐round next to the Warsaw Ghetto

- A collection of bizarre or unsettling posters from Fascist Italy; ‘Russian folk, Stalin orders you to die in order to save the Jew!’ (Serbia, 1942); a typical example of OUN‐B propaganda, dated 1941

- Those Who Said “No!”: Germans Who Refused to Execute Civilians during World War II

- Some Fascists contemplated keeping the earth’s last remaining Jews in a zoo

- The Fascists were the only force in history to deploy a sonic weapon in the field of battle

- Scandinavia & the U.S. sterilized more people than Fascist Italy

- Suicide figures of German Fascists in 1945

- The Last of the Wehrmacht to Surrender in WWII; Europe’s last Axis troops surrendered in September 4, 1945

Foreign policy

- Fascist Italy’s annexation of Fiume

- Greece & Fascist Italy signed a Treaty of Friendship, Conciliation, & Judicial Settlement

- Fascist Italy funded efforts to achieve cultural hegemony in Eastern Europe

- Fascist Italy & the Kingdom of Romania signed a ‘Pact of Friendship & Cordial Collaboration’

- The Treaty of Defensive Alliance between Fascist Italy & Albania

- The Penetration of Italian Fascism in Nationalist China

- The Fascists skillfully manipulated many Italian‐Americans into promoting Fascism

- Britain’s, France’s, & the Fascists’ Four‐Power Pact

- Introducing the Anti‐Komintern: Fascism’s own little ‘NGO’

- Poland & the Third Reich signed a nonaggression pact

- Polish–German film relations in the process of building Fascist cultural hegemony in Europe

- Poland’s ruling class let Fascists spread propaganda in its country

- Fascist Italy hired an American to train dozens of its cadets

- The Fascists spied on Italians living thousands of miles away from Italy

- Latinism & Hispanism in the Hispano‐American Right in Interwar Spain & Argentina

- Italian Fascist propaganda in Finland (1933–9)

- The Mussolini–Jabotinsky Connection: The Hidden Roots of Israel’s Fascist Past; Zionist support for Italian Fascism; the Fascists created Zionism’s first naval academy

- Zionist collaboration with the Third Reich: The ‘Jewish Agency for Israel’ maintained friendly relations with the Third Reich’s head of state as early as 1933, Zionists saw the victory of Fascism in Germany as a ‘fertile force’ for Zionism, the Third Reich generally supported Zionism, the Third Reich produced Zionist films, it trained (Zionist) Jews in agriculture to help settle them in Palestine, & ‘The ardent Zionists […] have objected least of all to the basic ideas of the Nuremberg Laws’

- How the Third Reich supported China’s anticommunists

- The Anglo‐German Naval Pact of 1935

- How Racist Policies in Fascist Italy Inspired & Informed the Third Reich

- The Fascists drew upon British Kenya & South Africa to implement racial policies in Ethiopia

- A sample of Italian Fascist colonialism: nursing & medical records in the Imperial War in Ethiopia

- Maltese support for Fascism & Rome’s support for Maltese fascism

- Romanian students & researchers in the Third Reich became tools of Fascist propaganda

- The Fascists partially created one of South Africa’s worst organizations

- Some Zionists compared their ideology favorably to German Fascism

- Transnationalizing fascist martyrs: an entangled history

- The Spectacle of Global Fascism: The Italian Blackshirt mission to Japan’s Asian empire

- Paris & Fascist Italy’s Franco‐Italian Declaration (“an outright military alliance”)

- Fascist Italy helped train Ukrainian & Croatian ultranationalists

- The Indians (of South Asia) who fought for the Axis

- A brief guide to the Blueshirts: Ireland’s Fascists

- Conceptions & Practices of International Fascism in Norway, Sweden & the Netherlands, 1930–40

- Fascism’s alleged ‘War on Slavery’ during the 1930s; the various native reactions to Fascism’s invasion of Ethiopia, from resistance to collaboration

- The Anti‐Comintern Pact

- The Rome–Berlin Axis

- Russian anticommunist collaboration with Spanish fascists (1936–1944)

- The Dalai Lama & the Fascists

- The Third Reich was a useful ally to the Spanish fascists

- Fascist Plans for Mass Jewish Settling in Ethiopia (1936–1943)

- Imperial Japan helped Finland decrypt Soviet military codes in its war on the Soviets

- Collaboration between Polish anticommunists & Japanese Imperialists in the 1930s & 1940s

- A guide to the ‘Honorary Aryans’

- Britain, France, & Fascist Italy gave part of Czechoslovakia to the Third Reich

- Paris & the Third Reich signed a Franco‐German Declaration

- Estonia & Latvia ratified nonaggression pacts with the Third Reich

- Why Berlin signed a nonaggression treaty with Moscow

- Why Thailand aligned with the Axis

- Ukrainian fascists in Poland fled towards the Third Reich for safety from the Soviets

- The Tripartite Pact

- France’s New Caledonia: The missing link between the Third Reich & the Empire of Japan

- The Axis’s national policy towards the Russian minority in the Baltic States

- The Empire of Japan’s counterinsurgency before 1945 & its persistent legacies in Asia

- How Fascist Italy recruited Greeks to shill for the Axis

- The Netherlands had one of the highest numbers of Waffen SS volunteers in Western Europe

- Fascist Italy was a valuable ally to the Third Reich

- Denmark’s volunteers in the Waffen SS

- The Slovak Republic’s Axis membership

- The Kingdom of Hungary’s Axis membership

- The Kingdom of Romania’s Axis membership

- Percentage of ‘non‐Germanic’ troops who helped start Operation Barbarossa

- Liechtenstein was complicit in Axis war crimes

- The Estonian Security Police’s collaboration with the Axis

- Why the Empire of Japan went to war against Imperial America

- Foreigners who joined the Wehrmacht & Waffen‐SS by January 1942

- The Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism: France’s truly pathetic Wehrmacht formation

- Turkey’s ‘Treaty of Friendship’ with the Third Reich

- Fascists forced thousands to build a railway in Finland, barely used it, & then destroyed it

- Handbook on Axis imperialism

- ‘Neutral’ European states that assisted the Third Reich

Atrocities

- Why the Fascist bourgeoisie committed the Holocaust (highly recommended)

- Masterpost on Italian Fascism’s atrocities (highly recommended)

- The brava gente myth: Fascist Italy’s equivalent to the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ lie

- The Fascists repeatedly assaulted Libyan Jews in the 1920s & later

- The Fascists’ suppression of Libya prepared them for their invasion of Ethiopia

- Continuities & Discontinuities: Antiziganism in Germany & Italy (1900–1938); Roma & Sinti in Fascist Italy: from expelled foreigners to dangerous Italians

- The Imperial invasion of Manchuria; Bodies in the Service of the Japanese Empire: Colonial Medicine in Manchuria

- The Fascist suppression of the Free Union of German Workers

- The Third Reich legalized the sterilization of disabled people

- The Fascists sometimes explicitly encouraged Jews to attempt suicide

- The Third Reich’s racism against the Japanese

- The first Nuremberg Laws

- Transgender People, the Third Reich, & the Holocaust; the life & death of a transgender woman in the Third Reich; the Fascists oppressed lesbians; German Fascism’s early assault on LGBT rights

- The Third Reich intentionally neglected thousands of tuberculosis patients

- The fate of black Germans under Fascism; brief summary of the Third Reich’s persecution of black humans; as early as 1933, the Third Reich killed a biracial communist for his antifascism

- The unique difficulties that legally ‘Jewish’ Germans suffered under Fascism

- The Fascists’ massacre of Addis Ababa

- Kristallnacht

- Comparisons between the “State of Israel” & Fascist Italy; comparisons between the “State of Israel” & the Third Reich

- Rome ordered all ‘foreign’ Jews to leave Italy within six months

- The Third Reich’s most infamous serial killer

- The Empire of Japan killed millions of people; it invaded Nanking, tormenting & massacring hundreds of thousands; Japanese Imperialists promoted a racism based on Japanese supremacy; Japanese Imperialism (indirectly) oppressed gay folks

- The Reich–Slovakian joint invasion of Poland

- The Polish government’s antisemitism was a major factor leading to the Shoah; Poland’s police force had a key rôle in the Fascist oppression of Jews

- The Third Reich kidnapped & attempted to forcibly assimilate thousands of Polish children

- The Fascist destruction of Poland’s infrastructure

- A brief overview of Italian Fascist atrocities in Greece; Axis occupation resulted in an increase in infectious diseases among Greeks

- The Fascists first tested Zyklon‐B on Soviet POWs

- The Warsaw ghetto

- France’s ruling class willingly committed its own fascist atrocities without outside pressure

- Alsace, France became a testing ground for the Third Reich’s anti‐Roma policies

- Romanian fascists literally butchered hundreds of Jews in a parody of Judaism’s kosher butchering

- Oskar Dirlewanger: the Fascist whom even other Fascists thought was cruel & depraved

- The misogynist revenge that the fascists inflicted on women in Southwestern Spain; the Spanish fascists encouraged Moroccan men to abuse women

- The Western Axis’s invasion of the Soviet Union

- The Wannsee Conference: how the Fascist bourgeoisie worked on a new policy for exterminating Jews

- How Ukrainian fascists pioneered brutal terror techniques (later improved by the CIA)

- The Religious Dimension of the First Antisemitic Violence in Eastern Galicia (June–July 1941)

- This is how the Axis & its collaborators treated Soviet civilians

- The Third Reich attempted to erase concentration camp prisoners’ identities

- Finland deported more than 2.8k POWs (including many Jews) to the Third Reich

- The Finnish bourgeoisie interned 24,000 ethnic Russians in concentration camps, 4,200 of whom died

- What the Kapos did in Axis concentration camps

- How the Third Reich treated Soviet POWs vs. Western ones

- The Wehrmacht & the anticommunist persecution of the Roma; the Third Reich ordered all Roma to be deported to Auschwitz; Auschwitz survivor Mano Höllenreiner recalls Axis death camp for Roma

- Therapeutic Fascism: ‘re‐educating’ Communists in Axis‐occupied Serbia, 1942–44

- The Wehrmacht massacred thousands of civilians in Axis‐occupied Serbia

- Jacob Gens: the Third Reich’s deadliest Zionist collaborator

- A ‘Wannsee Conference’ on the Roma’s extermination? New research findings regarding 15 January 1943 & the Auschwitz Decree

- The Axis massacred thousands of Jews & Roma (many of whom were Muslim) in Simferopol

- The Axis exterminated thousands of Kharkiv’s Soviets

- The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, & the Axis’s Massacres in Ukraine

- A brief history of fascism & terrorism within Zionism

- Axis auxiliaries laughed after a Gestapo commander falsely pardoned a girl, then shot her

- The Third Reich ran tanks over Senegalese soldiers

- The Holocaust in North Africa

- The Axis massacred thousands of Jews in its liquidation of the Słonim Ghetto

- History of Fascism in Ukraine, Pt. II: The OUN during 1941–1945; Stepan Bandera; Ukrainian fascists supported antisemitism (while simultaneously claiming to oppose it…apparently)

- Finnish volunteers in SS units took part in Axis atrocities, Finland confirms…in 2019

- The Axis’s capture of Banská Bystrica & its defeat of the concurrent Slovak National Uprising

- The Third Reich deliberately bombed hospitals; the Axis intentionally sunk a Soviet hospital ship, massacring over 5,000 people

- The Third Reich publicly massacred antifascist juvenile delinquents in 1944

- A Zionist collaborated with the Axis to sacrifice 800,000 ordinary Jews in return for 600 prominent Zionists

- The Third Reich had its own kamikaze pilots

- ‘Murder of the Jews’: The testimony of Germans & Austrians who were part of Fascism’s murder machine

- Of the 5–6 million Jews that the Axis massacred, more than 160,000 were Sephardim

- Grandmother relating her experience as a Holocaust survivor

Profascism

- Mussolini’s Sources of Financial Support, 1914–1915; British capitalists in the 1910s paid Mussolini to assault antiwar protesters

- ‘Where Lenin’s system has won for itself international ostracism & armed intervention, that of Mussolini has been the subject of widespread enthusiasm’

- The Economist on Fascist Italy in 1922: ‘So far, so good.’

- ‘I can understand why a businessman would admire Mussolini & his methods. They are essentially those of successful business.’

- Britain’s capitalist press repeatedly praised Fascism

- The KKK freely compared itself to European fascism

- The Polish anticommunists of the short 20th century were very impressed with Fascism

- From Churchill to NATO: How the West built & empowered Italian Fascism

- How the New York Times reacted to the rise of Fascism; the New York Times repeatedly suggested giving the German Fascists a chance

- A conservative chancellor referred to violence against Fascists as an excuse to harm communists; the Weimar Republic rarely prosecuted fascists, but suppressed socialists regularly

- Most German adults voted in approval of Fascism

- The riot at Christie Pits: Canada’s worst (and little‐known) antisemitic incident

- How the U.S. Associated Press cooperated with the German Fascists

- The little country that voted overwhelmingly to join the Third Reich

- How The Economist reacted to the Fascists violating the Treaty of Versailles by taking the Rhineland

- U.S. Responses to the Policies & Practices of the Third Reich’s Eugenics

- Winston Churchill

- Queen Elizabeth’s Fascist Salute is a Reminder how Close Britain Sailed to the Fascist Wind; how Queen Victoria’s Grandson Became Hitler’s Pawn & Favourite Royal

- U.S. capitalist Prescott Bush supported the Third Reich

- The gay men who sided with their Fascist oppressors

- The Jews who fought for their Fascist oppressors

- How the Pentagon Helped Hollywood Launder the Third Reich’s Reputation

- Chase National Bank supported the Third Reich

- The Third Reich’s Labour Services’ influence on Swedish & U.S. politicians

- The bourgeoisie let Fascists build summer camps across the U.S. during the 1930s

- About 20,000 fascists held a rally at the Madison Square Garden in 1939

- Many powerful Icelanders sympathized with the Third Reich

- The representation of Jews in the Finnish press before 1939

- How the Vatican collaborated with the Fascists throughout the 1930s

- When the Fascists massacred thousands in Addis Ababa, the U.S. & British govts. ignored it to avoid offending them

- Chinese landlords frequently collaborated with the Imperialists

- London Deliberately Ignored Axis Factories so that the Wehrmacht could Attack the USSR; London intentionally played down atrocities in an Axis concentration camp on its soil

- Zionist militia’s efforts to recruit Fascists against Britain revealed by Zionist archives

- New York’s capitalists let Fascist Italy host a pavilion in their city in 1939

- IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad’s ties to fascism

- The U.S. held more Fascist prisoners of war than it held Jewish refugees; Fascist POWs in Alabama had more food than they could eat, permission to attend university courses, befriend locals & leave the camp to work

- ‘Captive Nations’: The Forgotten Origins of the ‘Victims of Communism’

- How Australia’s Fascists got away with supporting the Third Reich

- Italian anticommunists pardoned Fascists while punishing thousands of partisans

- U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy defended Fascist war criminals

- The Western Allies became unconcerned with neofascist shrines as they now focused their aggression on the Soviets

- Operation Paperclip in New Jersey

- The CIA used ‘moderate’ anticommunists to distract people from the Axis collaborators

- A fascist sympathizer suggested a monument to the ‘victims of Communism’ as early as 1970

- LaRouche’s ‘Ukrainian Nazi’ Legacy

- The University of Alberta’s $1.4 million‐dollar Fascist problem

- Anticommunists equating us with German Fascists martyrize Axis collaborators

- Zelensky & U.S. Congress salute profascist “Representatives of Diaspora”

- Neofascists in Ukrainian military bragged about Canadian training, report says

- The New York Times on Ukraine’s neofascist imagery: It’s ‘complicated’; NYT has found more neofascist troops to lionize in Ukraine; Hawkish Pundits Downplay Threat of War, Ukraine’s Neofascist Ties; Western Media Fall in Lockstep for Neofascist Publicity Stunt in Ukraine; Facebook Protects Neofascists to Protect Ukraine Proxy War

- ‘NAFO’ exposed

Legacy

- The Fascist roots of Columbus Day

- The U.S. Army continued keeping Jews in the Axis’s concentration camps

- British officials recycled Fascists for their control of Eritrea in the 1940s

- How fascists who beat Jews to death became America’s favorite “Freedom Fighters” in 1945; the U.S. did not defeat Fascism in WWII, it discretely internationalized it

- There was no equivalent to the Nuremberg Trials for Italian Fascists; the liberal bourgeoisie refused to prosecute Fascists for their atrocities in Ethiopia

- The Wehrmacht bred with hundreds of Finns

- The Shadow of Fascism over the Italian Republic

- Important elements of the Fascist era survived in postwar France

- The Third Reich influenced eugenics in Iberia’s anticommunist dictatorships

- The Western Allies reused the Empire of Japan’s system of forced prostitution

- How Austria’s Fascists got away with supporting the Third Reich

- W. Germany’s govt. was riddled with ‘former’ Fascists & its capitalist press was outraged to see Axis criminals treated as anything less than saints

- Latvia’s anticommunist resistance consisted of many Axis collaborators (whom NATO honored)

- Axis servicemen provided the CIA with its most critical information on the Soviet Union

- Canada knowingly admitted thousands of SS members

- Continuities between Fascism & the post‐1945 Italian police

- The Kingdom of Sweden welcomed Baltic war criminals who served the Axis

- U.S. authorities gave Axis war criminals comfortable jobs in post‐1945 Japan

- A Zionist authority helped a horrifying Axis war criminal escape justice

- How a Romanian fascist responsible for killing hundreds of Jews found a safe haven in the U.S.

- In 1948, at least 53% of South Korea’s police officers worked for the Axis

- Historian discussing how the U.S. intentionally recruited ‘former’ Fascists & Axis collaborators; interview with the author of Old Nazis, New Right, & the Republican Party; how a Slovakian fascist war criminal became a CIA asset

- Ratlines, NATO, & the Fourth Reich; NATO’s Fascist Inheritance & the Long War on the Third World; NATO’s Fascist Beginnings

- MI6 hired Fascists

- Mossad intentionally hired Axis war criminal Walter Rauff

- The European Union’s Court of Justice’s first President was a Fascist

- Benito Mussolini has his own tomb (and it’s in good condition)

- Spain’s largest monument to fascism (still exists)

- Denmark failed to thoroughly purge its upper classes of Axis collaborators

- W. Germany’s Federal Court ruled that a 1940 deportation of Roma was not a racist atrocity

- When John F. Kennedy was asked when he would uproot Fascism from W. Germany, he said nothing

- Did Zionists cover up thousands of Axis war criminals in exchange for military technology?

- A former SS official became an advisor to Augusto Pinochet’s secret police

- Henry Kissinger’s ties to Fascism

- The interview that led to the arrest of Klaus Barbie, the Axis’s Butcher of Lyon

- W. Germany purged thousands of irreplaceable documents on Fascism & other subjects after 1990

- The Captive Nations Lobby: the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation’s fascist heritage; Victims of Communism’s founder Lev Dobriansky’s associations with Axis collaborators

- The Latvian SS‐Legion & issues regarding its modern glorification; Latvia invests in Axis commander biopic

- Yugoslav survivors of Fascist war camp lament Italy’s apathy

- The prolonged effects of trauma on Holocaust survivors

- An Analysis of Present‐Day Historical Narratives of Italy’s Colonial Wars

- In 2010, a Zionist judge proposed learning Fascist propaganda techniques & that same year, a few Zionists repeated ‘Hitler was right’ in public & the neocolonial police did nothing

- Finland’s cemeteries dedicated to Axis soldiers

- Some 1,500 statues & streets around the world honor Fascists — including in Germany & the U.S.; examples of monuments in Eastern Europe dedicated to Axis collaborators; Germany still exhibits Fascist sculptures; Italy still exhibits Fascist monuments; Japan still exhibits monuments dedicated to Axis war criminals; Axis collaborator monuments in Ukraine

- Mass graves left by the fascists discovered in Extremadura

- Archaeologists are exhuming the bodies from Spain’s fascist concentration camps

- Analysis of skeletal remains from the Battle of Britain: A temporary cemetery of Fascist aviators

- A New Anti‐Bolshevik Bloc of Nations?

- Ottawa apologizes for honouring another Axis collaborator

- Survivors of the Axis’s siege of Leningrad continue to suffer worse health even after seven decades

- Auschwitz museum justifies the extermination of Palestinians

- The Third Reich’s antisemitic indoctrination still survives in some elderly Germans

- The Axis’s barbed wire continues to harm Norway’s wildlife

- Even from beyond the grave, Fascists are still massacring people & inhibiting scientific research

- Fascist‐era parenting is still harming German youths today, & the Fascists themselves had abusive parents

Neofascism

- Operation Gladio; the CIA’s Secret Fascist‐Collaborating Terror Armies in Europe & Beyond

- How NATO worked with neofascists to crush communism in Turkey

- Swedish neofascist solidarity with the Chilean military junta

- The Zionists did nothing to help as Argentine neofascists terrorized thousands of Jews

- Refresher course on neofascist antisemitism

- Anders Breivik

- The Maidan Massacre in Ukraine: Revelations from Trials & Investigation

- A neofascist opened fire on a synagogue & massacred 11 people

- The road to neofascism: How the war in Ukraine has changed Europe; what you should really know about Ukraine; the roots of fascism in Ukraine: From Axis collaboration to Maidan; successive govts. in Ukraine have accommodated neofascists to counter Soviet nostalgia; examples of Ukraine’s head of state awarding vile antisemites; how Zelensky made peace with neofascist paramilitaries on front lines of war with Russia; how neofascists made their home in Ukraine’s major western training hub

- Ukraine Neofascists Infiltrate Every Level of Military & Government; a look at the Svoboda party: Ukraine’s second largest bundle of neofascist fuckwads; the Bandera cult, memory warriors, & ‘patriotic education’ in Ukraine; Bandera’s ‘Insurgency‐in‐Waiting’: OUN‐B & the ‘Capitulation Resistance Movement’; the Ukrainian Fascist Advisor from Azerbaijan

- Blackwater is in the Donbas with the Azov Battalion

- Famous Ukrainian Neofascist Visits U.S.

- Why is there now such an affinity between antivaxxers & neofascism?

- How USAID contributed to neofascism in Ukraine

- The neofascist ‘American Banderite Network’; defense contractors trying to ‘reactivate’ OUN‐B in Pittsburgh area

- ‘Nazigate’ & the ‘Bandera Lobby’; Ukrainian ultranationalism & Canada

- Meet Oleh Medunytsia, OUN‐B’s first Leader from Ukraine in over 20 years

- Neofascism strengthening in Germany (and elsewhere); neofascism is becoming more popular & powerful in Europe; international neofascists show solidarity with Ukrainian neofascists; the Rise of Neofascism in Italy

- “Now, All of You Are Azov”: Ukrainian Neofascists Tour U.S.; Azov is getting public funding from NAFO & other suckers & has been improving its relations with “human rights” think tanks

- The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation’s links to Hungarian neofascism

- What German neofascists have inherited from Fascism

- Nordic Resistance Movement: neofascists who hope to erect a pan‐Scandinavian ethnostate

- Adam Smith to Richard Spencer: Why ‘Libertarians’ (read: propertarians) turn to the Alt‐Right

- What is the Lukov March & why did the authorities ban it in Bulgaria?

- Neofascist Andy Ngô photographed with child molester Amos Yee

- Neofascists partook in anti‐transgender rally in Melbourne, Australia

- Zionist support for Azov

- Zionist neocolony contemplated forging ties with neofascist party accused of Holocaust denial

- Beware of neofascist grifters pretending to care about Palestine

- Spanish neofascist mercenary among others helping neocolonists in Gaza

- A reminder that neofascism is alive & well in the U.S.: Former(?) Neofascist Leader Holds U.S. Dept. of Justice’s ‘Domestic Counterterrorism’ Position; Neofascists Parade around Florida Chanting ‘Jews Will Not Replace Us’; U.S. congressman ‘unaware’ that he was posing for photo with neofascists; Texan Republican leaders reject ban on associating with Nazi sympathizers; neofascist march at the Tennessee State Capitol

Feel free to suggest any resources that you have in mind or how I could structure this thread better. Lastly, if you have any questions on fascism, profascism, parafascism (e.g. Japanese Imperialism), protofascism, or neofascism, you are welcome to ask me here or in private.

(This takes approximately seven minutes to read.)

We all know that the Shoah was not the first instance of mass violence against Jews in history, but I suspect that few of us have wondered what the largest loss of Jewish life was before then. The answer lies in the pogroms of the 1910s and the early 1920s: with the possible exception of the Polish–Cossack War of the mid‐17th century, this was the deadliest massacre of Jews before the 1940s. Quoting Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe in The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918–19: Prelude to the Holocaust, pages vii–viii:

The pogroms […] between 1917 and 1921 represent the largest and bloodiest anti-Jewish massacres prior to the Holocaust. The estimated number of Jews murdered in Ukraine in the aftermaths of World War I ranges from 50,000 to 200,000,¹ with many more Jews suffering violence, rape,² and loss of property.

Altogether 1.6 million Jews were affected by these violent events. Although it is impossible to determine the exact number of victims of these pogroms, there is no doubt that this was the largest outbreak of anti-Jewish violence before the Shoah[.]

[…]

Being overshadowed by the Holocaust, the pogroms in Ukraine are still not widely known. This unfortunate state of affairs is due to a number of factors. […] The relative lack of research on these events provides a further explanation of why the […] pogroms are much less known than the persecution [that] the Jews suffered at the hand of the [Axis] and other perpetrators during the Shoah.

If, over the last 70 years, research on the Holocaust has resulted in several thousand publications, which can be housed only in the library of a large institute such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the publications relating to the pogroms of 1917−1921 would fill no more than two or three shelves.

As you can see, this catastrophe is so obscure that it does not even have an official name, and Herzlians theirselves hardly ever discuss it for more than a few seconds. (A rare exception is the Times of Israel’s interview with Jeffrey Veidlinger in 2021.) I have dubbed it the ‘proto-Shoah’ for convenience’s sake. I suspect that if the upper classes regularly promoted its memory, it would raise awkward questions as to why they did not impose an ethnostate on Palestine in the 1920s if the Shoah was indeed the primary (or sole) reason for that in 1948.

The proto-Shoah, contrary to what Rossoliński-Liebe implied, was neither limited to the Ukraine nor did it last for only four years. On the contrary, we could argue that it started as early as 1914 before persisting all the way up to 1923, and it affected other regions, such as Poland:

In the last week of November, there occurred in the eastern Galician city of Lemberg (or, in Polish, Lwow), amid fierce fighting for control of the region between the Poles and Ukrainians who — along with very numerous Jews — jointly inhabited it, the most violent and deadly of all Polish pogroms of the postwar- and indeed the interwar years.

In three days 72 Jews were murdered and 443 others injured; 38 houses were burned, and in the pogroms aftermath 3,620 damage claims were officially submitted. It was, together with lawless civilians, mainly troops of the Haller legions who, with the connivance or toleration of their military superiors, carried out the pogrom.

One has only to recall the extermination of the Jews by Konstantin Konstantinovich Mamontov’s cavalry units during his famous raid through the rear of the Red Army in the fall of 1919. In this case, the massacre of the Jews occurred on Great Russian territory (Elets and other cities), and thus Ukrainian territory could have had nothing to do with these slaughters.

The mob that attacked the Jews in the villages of Diszel and Marcali in late summer of 1919 apparently wanted to force their “racial enemies” out of their communities (and in the process line their own pockets). Yet, in the end, they not only expelled middle-class Jews and stole their cash and valuables, but they also brutally murdered two families[.]

The Kingdom of Romania:

Although hostilities ceased in most of Europe in November 1918, Romanian soldiers continued fighting in Transylvania. The rhetoric of the war framed it as a crusade against communism after Béla Kun came to power in Hungary on 21 March 1919.

That November police distributed antisemitic posters around the country on the orders of the short-lived government led by Arthur Văitoianu (1864–1956). These posters identified members of Béla Kun’s Communist Party as Jewish and denounced all Jews as Bolsheviks who had to be liquidated. Isolated attacks on Jews and on Jewish property followed, including some by Romanian soldiers acting under orders, with no legal repercussions.⁵²

And so on. All told, I suspect that European antisemites exterminated more than 115,000 Jews from 1914 to 1923, and not merely in the Ukraine.

Many historians have interpreted this disaster as a precursor to the Shoah, but we need more research establishing links between both. Per Polly Zavadivker:

none of the recent scholarship has provided empirical evidence that links the anti-Jewish violence of that era to that of 1939–1945 as an origin event. Veidlinger, too, focuses on the descriptive history of the pogroms, but leaves the claim—the framing device of the book that makes it compelling to a wide readership—entirely unsubstantiated.

It would be quite an exaggeration to argue that the proto-Shoah ‘caused’ the Shoah, but we have a few clues indicating that the proto-Shoah probably influenced the Third Reich. For byspel:

Another German soldier in Galicia was disgusted with the Jewish merchants [whom] he encountered. “Before the peace,” he wrote, “I could not understand why there were pogroms in Russia. Since I have seen the Jewish way of doing business, it is no longer a puzzle how a hard-working farmer could beat one of these pests to death.”

The soldier concluded with a sentiment expressed by leading figures in the Third Reich: “Here is further proof [the encounter with Jews] that anti-Semitism is always a healthy reaction to seeing the Jewish masses represented. This, too, is a legacy of the front!”³⁸ While these excerpts traded in traditional anti-Semitic tropes, the “masses” of Jews cited in this context soon devolved into the specter of transient revolutionaries threatening the German frontier.

Der Frontsoldat erzählt published that soldier’s sentiment in 1939. Clearly, there were at least a few Third Reich officials familiar with the proto-Shoah, and it would be a most astounding coincidence if none of the leading officials were even aware of it. Quoting Michael Kellogg’s The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and the Making of Nationalism Socialism, 1917–1945, page 191:

In an article in an August 1923 edition of the Völkisch Observer, “The Ukraine and Russia,” Rosenberg, presumably, on behalf of the “editorial staff,” drew attention to Poltavets-Ostranitsa’s newspaper The Ukrainian Cossack. The essay argued: “We believe that Great Russians and Ukrainians will finally decide for a more federal arrangement of their empire after the smashing of Jewish-Bolshevik Moscow.” The piece emphasized that the Ukraine, where “patriots” were struggling against a “centralized dictatorship,” occupied a similar position to Bavaria, where rightists were opposing the “November Republic.”¹²¹

As far as I can tell, none of the politicians in Berlin had any major complaints against the anti-Jewish tyrant Symon Petliura, and somebody there wanted to exploit the French library dedicated to him. Quoting Patricia Kennedy Grimsted’s ‘The Odyssey of the Petliura Library and the Records of the Ukrainian National Republic during World War II’:

When France was invaded by [the Fascists] and Paris fell to occupying forces in 1940—still during the period of the [German]–Soviet pact—Hitler was already planning his Drang nach Osten. As one phase of the preparations, [Axis] specialists had targeted various Slavic émigré libraries in France and other countries in Western Europe as important intelligence sources, and their followers as potential allies in the [Axis’s] subsequent anti-Soviet campaign.

As librarian Ivan Rudychiv confided in his diary in January 1941, the notion “was circulating among Russian émigré circles [in Paris] that Petliura was the first great nationalist, and that Hitler was a student of Petliura.” Furthermore, it was rumored, Hitler was already endorsing Ukrainian independence.¹⁶

For [Axis] propagandists, although the [Ukrainian National Republic] was traditionally pro-French and pro-Polish and anti-German, Petliura’s antisemitic reputation made him a symbol to be manipulated for the [Axis] cause. The Petliura Library had an additional appeal, in that its martyr patron died at the hand of an acquitted assassin who sought revenge for Petliura’s alleged rôle in anti-Jewish pogroms.¹⁷

Speculations that his assassin had been encouraged by Soviet intelligence sources could also increase the usefulness of Petliura’s martyrdom to [Axis] propagandists anxious to exploit anti-Soviet sentiments abroad and in the soon-to-be occupied Ukrainian lands.

(Keep in mind that the Kingdom of Italy and the Twoth Reich were on opposing sides in World War I, and later that was all water under the bridge. Thus, it would be unsurprising if the Third Reich’s head of state was indeed ‘a student of Petliura’ as rumoured here.)

As the Western Axis powers steadily occupied in the Soviet Union, it inspired anti-Jewish fury in Ukrainian anticommunists. Quoting David Engel’s The Assassination of Symon Petliura and the Trial of Scholem Schwarzbard 1926–1927, page 95:

From 25 to 27 July 1941, Ukrainian police in the service of the recently-completed [Axis] occupation of Lwów were joined by mobs of Ukrainian peasants from nearby villages in brutal attacks upon Jews in the city streets and in their homes, in a fashion reminiscent of the pogroms of two decades previous. Upwards of 2,000 Jews were killed over the course of three days. The events were presented at the time as an act of revenge for the death of a Ukrainian national hero on the fifteenth anniversary of his murder. They have been known ever since as “the days of Petliura.”³³⁹

(Emphasis added in all cases.)

While the evidence linking the proto-Shoah to the Shoah may be circumstantial and insufficient (for now), Stefan Ihrig’s investigation of the links between the Meds Yeghern and the Shoah has shown that an impressive quantity of circumstantial evidence can make a ‘smoking gun’ practically superfluous. A great potential for research exists here.

There is more that I want to write about the proto-Shoah, but this topic is getting lengthy enough as it is. Suffice it to say that even if by some bizarre coincidence all of the leading Axis officials were unaware of this catastrophe, there can be no doubt that it further normalised anti-Jewish violence for many: if so many anticommunists could get away with plundering as well as slaughtering so many Jews, it would have been all too easy for Axis officials or collaborators to look at that and think that they could do the same.

Further reading: In the Midst of Civilized Europe: the Pogroms of 1918–1921

Quoting Jerzy Łazor’s ‘Control and Regulation of Capital Flows between Poland and Palestine in the Interwar Period’ in Foreign Financial Institutions & National Financial Systems, pages 233–235:

In the 1930s impoverished Polish Jews found it hard to procure the necessary funds, while richer strata of the Jewish community were less interested in migration. Now the situation worsened. Both Polish and Zionist officials understood that a new solution was needed, and studied the [Fascist] system known as Haʻavarah as a successful model for such an arrangement.

Within Haʻavarah, which had been created in 1933, emigrating German Jews would transfer their assets to a central agency, which used them to finance exports of [Fascist] products to Palestine. Emigrants would then receive money from the sale of these products, losing on average about 35 per cent of their initial capital payments. This allowed [Fascist] goods in Palestine to be sold below market prices, and their exports surged.

The system provoked a serious debate both in the Jewish diaspora, and in the jishuv (the Jewish society in Palestine). It was created at roughly the same time as the boycott movement, initiated by European Jews, and aimed at limiting imports from [the Third Reich]. Jews in Europe felt betrayed. Despite its moral and political ambiguities, Haʻavarah proved to be an economic success. It allowed some 20,000 people to come to Palestine, bringing with them around six million £P.²⁸

As early as May 1936, a Palestinian delegation came to Poland to negotiate a transfer agreement. It included two former Polish MPs: Fiszel Rottenstreich and Icchak Grünbaum. The third member of the delegation — Dr. Salheimer — was particularly interesting, since his home institution, the Anglo-Palestine Bank, was responsible for the Palestinian part of Haʻavarah operations.

The situation soon became more complicated. Joszua Farbstein, another former Polish MP and erstwhile head of the Department of Industry and Commerce of the Jewish Agency Executive, came to Poland at the same time. The press was rife with speculation and accused Farbstein of attempting to negotiate with the Polish government on his own account. I found no traces of this in Polish archives.

Farbstein was not the only Palestinian guest in Poland at the time: Moussa Chelouche, head of the Palestinian–Polish Chamber of Commerce in Tel Aviv, was another. Chelouche, an important figure in the Ashrai Bank and the Immigrant’s Bank Poland–Palestine Ltd, allegedly tried to dissuade the Polish government from accepting the Anglo-Palestine Bank as a major component of the new transfer. Again, I was not able to find any confirmation of these actions, beyond allegations in the Palestinian press.

Finally, Poland was in negotiations over their ‘marriage of convenience’ with the revisionist movement. Both sides had to tread lightly.²⁹

After Rottenstreich’s anti-Polish speech in August 1936 the Poles refused to talk to him. Further negotiations were thus concluded with Grünbaum alone.³⁰ Grünbaum was no novice. An important figure in Jewish interwar politics in Poland, he had been one of the creators of the minority bloc in the Sejm.

At the same time, institutions in Palestine — including the Anglo-Palestine Bank and the Executive of the Jewish Agency — tried to influence Polish officials through their representatives in Palestine. Since Bank P.K.O. was a plausible Polish choice for the main bank of the new transfer system, particular pressure was put on this subject. The director of its Tel Aviv branch, Tadeusz Piech, was told that his bank was too small, and reminded that it had only survived the banking runs in 1935–1936 with the help of the Anglo-Palestine Bank.³¹

Palestinian Jews insisted that the new arrangement should not threaten Haʻavarah. Since the list of Polish and [Fascist] goods competing on the Palestinian market was fairly long, a successful agreement with Poland could hurt Haʻavarah. Many considered it crucial for the development of the jishuv: it guaranteed a substantial flow of capital combined with a relatively low level of capitalist immigration: an outcome which went hand in hand with ruling Zionist ideology.

Polish consuls noted that the Jews’ insistence on the rôle of the Anglo-Palestine Bank was a sure sign that the Haʻavarah was considered more important than a possible agreement with Poland (although this logic seems a bit flawed). It was probably understood in Palestine that Poland would not be able to provide the amount of capital [that] the Jews needed (and which they were getting from [the Third Reich]). Moreover, with the Haʻavarah playing such an important rôle, there was no place for a particularly strong rise in Polish exports.³²

(See pages 235–245 if you have time to read more.)

If local conditions and context help explain why the Bigio didn’t return to Piazza Vittoria in 2013, national trends of the kind outlined in the introduction point to why the idea was first entertained. The Paroli administration’s commitment to the project was of a piece with the ‘new’ right’s efforts to overturn traditional anti-Fascist historical memory. Reclaiming public space was a small but important element of this.

In some FI and AN-controlled areas of Italy, streets, squares, and parks were renamed after Fascists (and neo-Fascists), new plaques commemorating Fascist-era events or individual Fascists were erected and old plaques and inscriptions restored. In one notable case, in 2012, the AN mayor of Affile in Lazio funded the construction of a mausoleum for the Fascist military leader and alleged war criminal Rodolfo Graziani.⁷⁹

The justificatory narratives used by local leaders typically stressed the same points: these were not ideological acts but rather a sign of a new calmness within Italy; Fascism was now history rather than politics, to be viewed without prejudice or fear.

“The story we got about World War II is all wrong,” a guest told Tucker Carlson on his podcast two weeks ago. “I think that’s right,” replied Carlson. The guest, a Cornell chemistry professor named David Collum, then spelled out what he meant: “One can make the argument we should have sided with Hitler and fought Stalin.” Such sentiments might sound shocking to the uninitiated, but they are not to Carlson’s audience. In fact, the notion that the [Axis] dictator was unfairly maligned has become a running theme on Carlson’s show—and beyond.

Last September, Carlson interviewed a man named Darryl Cooper, whom he dubbed “the most important popular historian working in the United States today.” Cooper’s conception of honest history soon became clear: He suggested that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill might have been “the chief villain of the Second World War,” with Nazi Germany at best coming in second. The day after the episode aired, Cooper further downplayed Hitler’s genocidal ambitions, writing on social media that the [Axis] leader had sought peace with Europe and merely wanted “to reach an acceptable solution to the Jewish problem.” He did not explain why the Jews should have been considered a “problem” in the first place.

“What is it about Hitler? Why is he the most evil?” the far-right podcaster Candace Owens asked in July 2024. “The first thing people would say is: ‘Well, an ethnic cleansing almost took place.’ And now I offer back: ‘You mean like we actually did to the Germans.’” A repeat guest on Carlson’s show, Owens defended him after his conversation with Cooper. “Many Americans are learning that WW2 history is not as black and white as we were taught and some details were purposefully omitted from our textbooks,” she wrote on X (formerly known as Twitter).

These Reich rehabilitators are not fringe figures. Carlson’s show ranks among the top podcasts in America. He spoke before President Donald Trump on the final night of the 2024 Republican National Convention, and his son serves as a deputy press secretary to Vice President J. D. Vance, who owes his office in part to Carlson’s advocacy.

Owens has millions of followers on YouTube, Instagram, and X (formerly known as Twitter), and over the past six months, she has been interviewed by some of the nation’s most popular podcasters, including the comedian Theo Von and the ESPN personality Stephen A. Smith. Her output has attained sufficient notoriety that she is currently being sued by French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife, Brigitte, over her repeated claims that the French first lady was actually born a man. Cooper, the would-be World War II revisionist, publishes the top-selling history newsletter on the entire Substack platform.

Why does a potent portion of the American right seek to rehabilitate Hitler? The [Axis] apologetics are partly an attention-seeking attempt at provocation—an effort to signal iconoclasm by transgressing one of society’s few remaining taboos. But there is more to the story than that. Carlson and his fellow travelers on the far right correctly identify the Second World War as a pivot point in America’s understanding of itself and its attitude toward its Jewish citizens. The country learned hard lessons from the […] Holocaust about the catastrophic consequences of conspiratorial prejudice. Today, a growing constituency on the right wants the nation to unlearn them.

Before [September 1939], the United States was a far more anti-Semitic place than it is now. Far from joining the conflict to rescue Europe’s Jews, the country was largely unsympathetic to their plight. In 1938, on the eve of the Holocaust, Gallup found that 54 percent of Americans believed that “the persecution of Jews in Europe has been partly their own fault,” and that another 11 percent thought it was “entirely” their fault. In other words, as the [Third Reich] prepared to exterminate the Jews, most Americans blamed the victims.

The same week that the Kristallnacht pogrom left thousands of synagogues and Jewish businesses in ruins, 72 percent of Americans opposed allowing “a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live.” Months later, 67 percent opposed a bill aimed at accepting child refugees from Germany; the idea never made it to a congressional vote. Many Americans worried, however illogically, that fleeing Jews might be German spies, a vanishingly rare occurrence. Those with suspicions included President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who suggested in 1940 that some refugees could be engaged in espionage under compulsion from the [Third Reich], “especially Jewish refugees.”

This climate of paranoia and hostility had deadly consequences. In 1939, the U.S. and Canada turned away the M.S. St. Louis, which carried nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees. The ship was forced to return to Europe, where hundreds of the passengers were captured and killed by the Germans. Restrained by public sentiment, Roosevelt not only kept the country’s refugee caps largely in place but also rejected pleas to bomb the Auschwitz concentration camp and the railway tracks that led to it. When the United States finally entered the war, it did so not out of any special sense of obligation to the Jews but to defend itself after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

That indifference to the Holocaust was immediately dispelled when the Allied Forces liberated several of the [Axis] camps where millions of Jews had been murdered. Entering the gates of these sadistic sites, American service members came face-to-face with unspeakable [Axis] atrocities—rotting piles of naked corpses, gas chambers, thousands of emaciated adults.

Denial gave way to revulsion. “I thought of some of the stories I previously had read about Dachau and was glad of the chance to see for myself just to prove once and for all that what I had heard was propaganda,” Sergeant Horace Evers wrote to his family in May 1945. “But no it wasn’t propaganda at all […] If anything some of the truth had been held back.”

Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied Forces in Europe and future U.S. president, personally went to Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald and the first Nazi camp liberated by American troops. “I made the visit deliberately,” he cabled to Washington, “in order to be in position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’”

Eisenhower then requested that members of Congress and prominent journalists be brought to the camps to see and document the horrors themselves. “I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald,” the legendary CBS broadcaster Edward R. Murrow told his listeners after touring the camp. “I reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it, I have no words.”

Two-thirds of Europe’s Jews had been murdered. American soldiers, drafted from across the United States, returned home bearing witness to what they had encountered. “Anti-Semitism was right there, it had been carried to the ultimate, and I knew that that was something we had to get rid of because I had experienced it,” Sergeant Leon Bass, a Black veteran whose segregated unit entered Buchenwald, later testified. In this way, the American people learned firsthand where rampant anti-Jewish prejudice led—and the country was transformed.

Americans began to understand themselves as the ones who’d defeated the Nazis and saved the Jews. Slowly but surely, anti-Semitism became un-American. But today, those lessons—like the people who learned them—are passing away, and a wave of propagandists with a very different agenda has arisen to fill the void they left behind.

Over the past few years, Tucker Carlson and his co-ideologues have begun insinuating anti-Semitic ideas into the public discourse. The former Fox News host has described Ben Shapiro, perhaps the most prominent American Jewish conservative, and those like him as foreign subversives who “don’t care about the country at all.” He has also promoted a lightly sanitized version of the white-supremacist “Great Replacement” theory that has inspired multiple anti-Semitic massacres on American soil.

Candace Owens has accused Israel of involvement in the 9/11 attacks and the JFK assassination, and claimed that a Jewish pedophile cult controls the world. (Like many pushing such slanders, she has apparently discerned that replacing Jews with Israel or Zionists grants age-old conspiracy theories new legitimacy.)

(I would like to politely remind readers that conflating Jews with Zionists is exactly what Herzlians want to see.)

In March, an influencer named Ian Carroll—who has a combined 3.8 million social-media followers, and whose work has been shared by Elon Musk—joined Joe Rogan, arguably the most popular podcaster in America, to expound without challenge about how a “giant group of Jewish billionaires is running a sex-trafficking operation targeting American politicians and business people.”

Before America entered World War II, reactionaries such as the famed aviator Charles Lindbergh and the Catholic radio firebrand Father Charles Coughlin inveighed against the country’s tiny Jewish population, accusing it of controlling America’s institutions and dragging the U.S. to war. “Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government,” Lindbergh declared of American Jews in 1941. “Why is there persecution in Germany today?” asked Coughlin after Kristallnacht. “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.” For these men and their millions of supporters, behind every perceived social and political problem lay a sinister Jewish culprit.

The 21st-century heirs of Lindbergh and Coughlin seek to turn back the clock to a time when such sentiments were seen by many as sensible rather than scandalous. These far-right figures have correctly ascertained that to change what is possible in American politics, they need to change how America talks about itself and its past. “The reason I keep focusing on this is probably the same reason you’re doing it,” Carlson told Darryl Cooper, the amateur Holocaust historian. “I think it’s central to the society we live in, the myths upon which it’s built. I think it’s also the cause of the destruction of Western civilization—these lies.”

Carlson couches his claims in layers of intellectual abstraction. Others are less coy. “Hitler burned down the trans clinics, arrested the Rothschild bankers, and gave free homes to families,” the former mixed martial artist Jake Shields told his 870,000 followers on X (formerly known as Twitter) last week. “Does this sound like the most evil man who ever lived?” The post received 44,000 likes. (Shields has also denied that “a single Jew died in gas chambers.”)

“Hitler was right about y’all,” said Myron Gaines, a manosphere podcaster with some 2 million followers across platforms, referring to Jews last year. “You guys come into a country, you push your pornography, you push your fuckin’ central banking, you push your degeneracy, you push the LGBT community, you push all this fuckin’ bullshit into a society, you destroy it from within.” These influencers are less respectable than Carlson, but their views are precisely the ones that more presentable propagandists like him are effectively working to mainstream. After Carlson’s guest last month suggested that the U.S. “should have sided with Hitler,” Shields reposted the clip.

Had Carlson and his cohort attempted their revisionism 20 years ago, they would have encountered a chorus of contradiction from real people who had experienced the history they sought to rewrite and know where its conspiratorial calumnies lead. But today, most of those people are dead, and a new generation is rising that never witnessed the Holocaust firsthand or heard about it from family and friends who did.

Late last year, David Shor, one of the Democratic Party’s top data scientists, surveyed some 130,000 voters about whether they had a “favorable” or “unfavorable” opinion of Jewish people. Hardly anyone over the age of 70 said their view was unfavorable. More than a quarter of those under 25 did. The question is not whether America’s self-understanding is changing; it’s how far that change will go—and what the consequences will be.

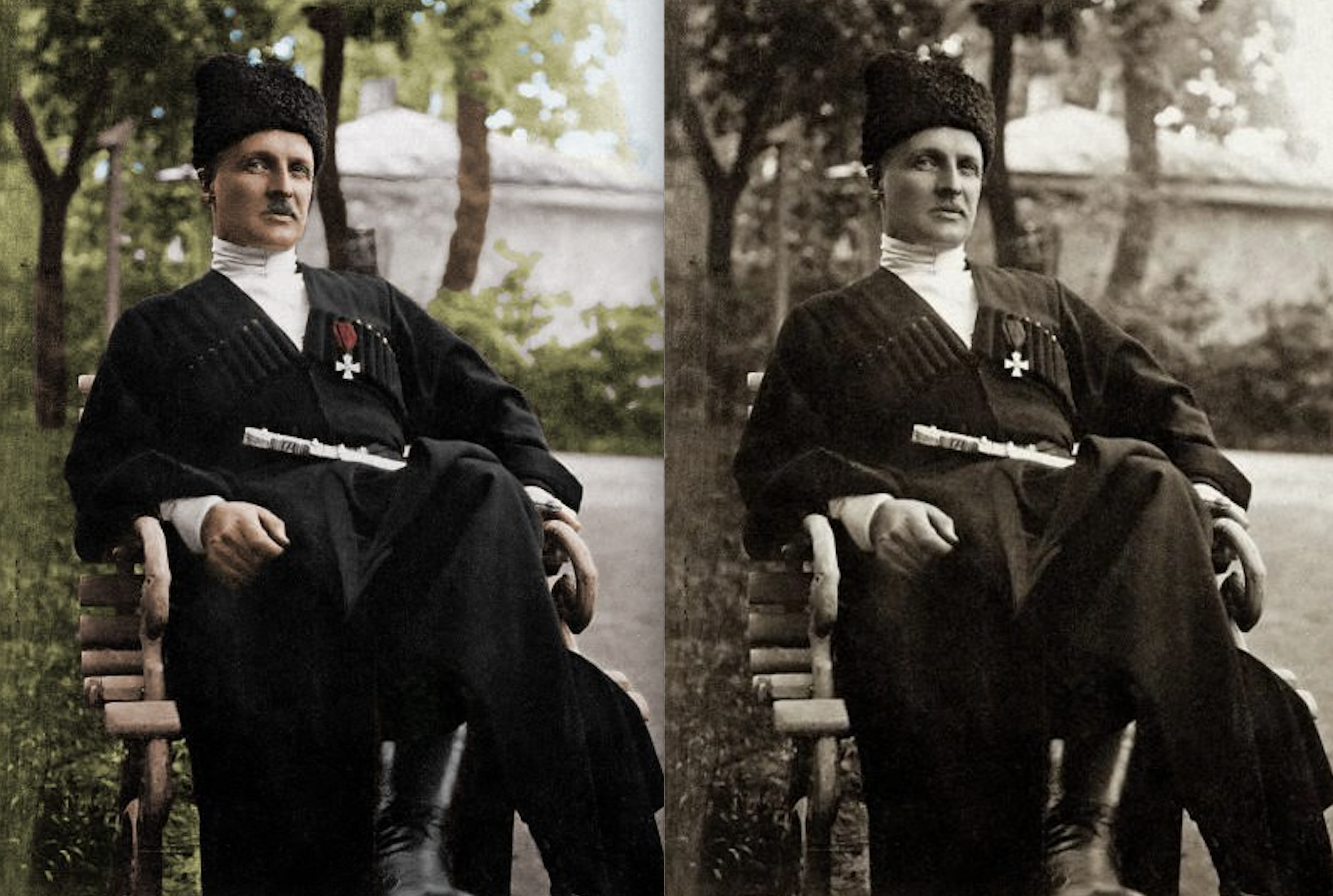

[Two decades] ago, Oleksandr Alfyorov was a young “Hetmanite,” or follower of Pavlo Skoropadsky (1873–1945), the [Central Powers’] puppet ruler of Ukraine in World War I, who later spent the interwar period cozying up to the [Third Reich]. Skoropadsky had a villa in Wannsee, the Berlin suburb that later hosted the conference dedicated to the “Final Solution.” Skoropadsky and his followers vied with the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) to be the [Axis’s] preferred Quislings in Ukraine.

The Hetmanites were a smaller, more openly pro-[Reich] monarchist movement (supported by [the Third Reich] in the 1930s) that just barely survived the Cold War in North America. In the 2000s, Alfyorov helped to revive Skoropadsky’s “Union of Hetman-Statesmen” in Ukraine and led its “conservative” youth group.

Pavlo SkoropadskyAlfyorov has reportedly “emphasized that the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance needs to expand the chronological framework, which was narrowed during the [Banderite] reforms of 2014–2015.”

He is not just thinking of Skoropadsky, but appears to be far more interested in the “thousand-year history” of Ukraine than the [Fascist]-era “liberation movement.” Given the prevalence of [anticommunist] [neo]paganism in the Azov movement, and those fascinated with Ukraine’s supposed “Aryan” roots, it makes you wonder about his relationship to those ideas. When Alfyorov laid out his five priorities for the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory (UINP, Ukrayinsʹkyy instytut natsionalʹnoyi pam'yati), two related to the Thousand-Year History.

- Strong inclusive national memory. Promote the thousand-year history of the Ukrainian people without looking back at centuries-old Russian narratives. Tell the history of Ukraine without looking to the East, as if Russia had never existed. Strengthen the mutual integration of the memories of Ukraine and Europe. We are not going to Europe — we are returning home.

[…]

- A broad contextual framework for history. We will not only talk about the history of Ukraine in the 20th century, but also focus on other periods of Ukrainian history. We will reveal to society the thousand-year-old tradition of Ukrainian statehood and its continuity.

In 2014, Alfyorov became the press secretary to the Azov Regiment (until 2015) and Andriy Biletsky (until 2018). In 2016, he joined the leadership of Biletsky’s “National Corps,” a new Azovite political party. One year later, the Azov movement formed the “National Militia,” which in 2020 relaunched as the paramilitary “Centuria.” As Leonid Ragozin put it, the Azov movement is “built on a very clear ideological foundation - far right politics and adoration of nazi collaborators.”

Alfyorov spoke at a press conference with the neo[fascist] leadership of Centuria in 2018. He might have first gotten involved with the UINP in 2019, when he lectured officers of the Joint Operational Headquarters of the Ukrainian armed forces on “The Role of Religion in the Formation of Ukrainian Statehood.” He thanked Roman Kulyk, a far-right UINP staffer, for the opportunity (more about him next time).

When the National Corps and Centuria formed new Azov units in 2022, which largely consolidated in the 3rd Assault Brigade, Alfyorov became an officer in the Special Operation Forces “Azov-Kyiv” Regiment, and later a “historian lieutenant” in Biletsky’s brigade. Alfyorov was put in charge of the 3rd Assault Brigade’s ideological “humanitarian training group,” or “Khorunza service,” which keeps the unit grounded in Azov’s “very clear ideological foundation.”

Centuria’s 2025 social media tribute to “Perun Day,” the Slavic god of war, and “Aryan,” an ideological officer from the 3rd Assault Brigade Khorunza serviceIn the spring of 2022, the Kyiv city administration pledged “to get rid of all dubious and false signs of Russian-Ukrainian friendship that affect our cultural consciousness and contribute to the spread of Russian propaganda and falsification of Ukrainian history.”

Furthermore, it established a “toponymic commission” or “expert working group” on “De-Russification” led by Azov-Kyiv Regiment officer Oleksandr Alfyorov. The group included “experts” from the UINP and various institutes of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU). Since 2010, Alfyorov worked as a research fellow at the NASU Institute of History, and apparently he joined the commission as its representative.

According to Alfyorov, “the work of the expert commission was undermined, and in some cases even neutralized.” Nevertheless, they identified almost 300 “city objects” to be renamed and offered two options for Ukrainians to choose from, by opening the “Kyiv Digital” app and locating the “vote for derussification” page. (Alfyorov rejects this term, because “there is a hidden reality that Rus’ and rus’ke [what belongs to Rus’] are ours.” He also objects to “decolonization,” because this would “connect us with Africa and Latin America.” So he prefers “de-imperialization.”)

As a result, the “Heroes of the Azov Regiment” and “Heroes of Mariupol” streets appeared in the capital, replacing those named after Marshals of the Soviet Union. In 2023, Alfyorov helped to rename Leo Tolstoy Square and its corresponding metro station in central Kyiv to “Ukrainian Heroes Square,” and Leo Tolstoy Street was changed to honor “Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky.”

[…]

The news broke in late May about Alfyorov’s appointment to lead the UINP. Apparently he wants to rehabilitate not just [Axis] collaborators, such as the Hetmanites and OUN-UPA, but Ukrainian soldiers who swore loyalty to Hitler. The historian Marta Havryshko reported in July, “The first bold move by the new head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory—Azov veteran Oleksandr Alferov, known for praising Hitler and curating an exhibition glorifying the Waffen-SS Galicia Division—was to rehabilitate Zenon Wrublewsky, a fighter from that very division.”

In 1958, then-foreign minister Golda Meir raised the possibility of preventing handicapped and sick Polish Jews from immigrating to Israel, a recently discovered Foreign Ministry document has revealed.

"A proposal was raised in the coordination committee to inform the Polish government that we want to institute selection in aliyah, because we cannot continue accepting sick and handicapped people. Please give your opinion as to whether this can be explained to the Poles without hurting immigration," read the document, written by Meir to Israel’s ambassador to Poland, Katriel Katz.

The letter, marked "top secret" and written in April 1958, shortly after Meir became foreign minister, was uncovered by Prof. Szymon Rudnicki, a Polish historian at the University of Warsaw.

In recent years, Rudnicki has been researching documents shedding light on Israeli–Polish relations between 1945 and 1967.

The document had not been known to exist before this time, and scholars of the mass immigration from Poland to Israel that took place from 1956 to 1958 were unaware of Israel’s intent to impose a selection process on Jews leaving Poland — survivors of the Holocaust and its death camps.

The "coordination committee" Meir refers to was a joint panel consisting of representatives of the government and the Jewish Agency.

Rudnicki’s study, undertaken together with Israeli scholars headed by Prof. Marcos Silber of the University of Haifa, has already been published in a book in Polish.

The Hebrew version of the book [was] published in a few months. However, the document containing the suggestion about the selection process does not appear in the book because it did not impact relations between the two countries.

"Although there are numerous documents on the issue of immigration, we did not find in the archives of Israel or Poland — where they also opened the party archive for us — any response to this request by Golda to the ambassador in Poland," Rudnicki told Haaretz. "In this respect, the document remains an internal matter of Israel," he said.

However, Rudnicki concedes that the content of the document surprised him as a scholar and a Jew.

"This is a very cynical document," he said. "It is known that Golda was a brutal politician who defended interests more than people."

Katz died more than 20 years ago, and no proof has been found that anything was done regarding the foreign minister’s query.

The 1956–1958 wave of immigration from Poland, also known as the "Gomułka Aliyah" was the second wave of immigration from Poland after World War II. In those years, due to a major lifting of restrictions on Jews leaving the country, some 40,000 Polish Jews came to Israel.

In the first wave, in 1950, Poland prevented anyone who had professions essential to Polish economy and society from leaving, including Jewish doctors and engineers. With the rise to power of president Władysław Gomułka and his initiation of reforms at the beginning of what became known as the "Gomułka thaw," the Polish government allowed people with professions more in demand to leave the country, including Jews who had taken up senior positions in the Communist Party.

"Until 1950, there was indeed selection by the Poles on the basis of professions in demand," Rudnicki said. "After 1956 the Poles imposed no limitations, and certainly did not intentionally send handicapped and aged people to Israel. That is an Israeli story, not a Polish one," the historian said.

During the years to which the document refers, waves of immigration were also underway from other countries, placing a heavy burden on the young state.

Statistics show that the rate of immigration at that time was similar to that at the height of immigration from the former Soviet Union from 1990 to 1999.

Quoting Michael Jabara Carley’s 1939: The Alliance That Never Was and the Coming of World War II, pages 44–5:

The war scare prompted the French government to sound out Poland about its support, though the Poles had already offered numerous indications of their intent. On May 22 Bonnet called in the Polish ambassador in Paris, Juliusz Łukasiewicz, to ask what the Polish policy would be. “We’ll not move,” replied Łukasiewicz.

The Franco-Polish defense treaty included no obligation in the event of war over Czechoslovakia. If France attacked [the Third Reich] to support the Czech government, then France would be the aggressor. Not apparently overreacting to this extraordinary statement, Bonnet then inquired about the Polish attitude toward the Soviet Union, stressing the importance of Soviet support, given Polish “passiveness.”

Łukasiewicz was equally categorical: “the Poles considered the Russians to be enemies [and we] will oppose by force, if necessary, any Russian entry onto [our] territory including overflights by Russian aircraft.” Czechoslovakia, Łukasiewicz added, was unworthy of French support.²⁴

If Bonnet had any doubts that the Polish ambassador was not accurately representing his government’s views, these were quickly put to rest by Field Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz. He told the French ambassador in Warsaw, Léon Noël, that the Poles considered Russia, no matter who governed it, to be “Enemy № I.” “If the German remains an adversary, he is not less a European and a man of order; for Poles, the Russian is a barbarian, an Asiatic, a corrupt and poisonous element, with which any contact is perilous and any compromise, lethal.”

According to the Polish government, aggressive action by France, or the movement of Soviet troops, say even across [the Kingdom of] Romania, could prompt the Poles to side with [the Third Reich]. This would suit many Poles, reported Noël: they “dream of conquests at the expense of the USSR, exaggerating its difficulties and counting on its collapse.” France had better not force Poland to choose between [the Soviet Union] and [the Third Reich], because their choice, according to Noël, could easily be guessed.²⁵

As Daladier put it to the Soviet ambassador, “Not only can we not count on Polish support, but we have no faith that Poland will not strike [us] in the back.” Polish loyalty was in doubt even in the event of direct [Fascist] aggression against France.²⁶

Pages 68–9:

Colonel Józef Beck was the Polish foreign minister and a key subordinate of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, the Polish nationalist leader who had died in 1935. Beck began his career as a soldier during the First World War, but after the war he was increasingly chosen for diplomatic work and in 1932 he became foreign minister.

Like Piłsudski, Beck was a Polish nationalist who hoped to reestablish Poland as a great power, as it had been in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Their efforts were unsuccessful, and this failure left Polish nationalists sour and quick to take offense.

Yet they tended to carry on the business of state as though Poland was a great power—dangerous conduct in the 1930s as [the Third Reich] grew stronger and more predatory. Beck leaned toward [the Third Reich] in the late 1930s, which brought Poland into conflict with the Soviet Union. Essentially the Polish government tried to ride the tiger’s back, and ultimately could not do so. If Poland then fell out with its other great neighbor, [the Soviet Union], it would be in grave danger.

[…]

In a meeting with the British ambassador on September 24, Beck said that Poland would not “tie its hands” regarding Teschen; “it did not have belligerent intentions but it could not agree that German demands being satisfied, Poland should receive nothing.”

Put another way, Beck said he did not intend to leave to [the Third Reich] the exclusive benefits of a dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. Anyway, added Beck, there was nothing to worry about because the Czech government had indicated verbally to the Polish minister in Prague that it agreed in principle to the cession of territory to Poland.

The Poles had other ways of sending their message to Paris: when the French military attache asked for information on German troop movements, his counterpart could say little in view of the French position on Teschen. If [the Third Reich] entered Czechoslovakia, this Polish officer added, Poland would take advantage of the situation to act in its own interests.

(Emphasis added.)

Quoting Wojciech Morawski in Foreign Financial Institutions & National Financial Systems, pages 156–7:

Ties between Polish and Italian banking date to before the First World War. Józef (Giuseppe) Toeplitz, a member of one of the leading Warsaw banking families, started working in Banca Commerciale Italian[a]. He become its chairman in 1917 and held the position until 1933. In 1919 BCI acquired Bank Zjednoczonych Ziem Polskich SA in Warsaw.